Four big ideas shaping the future of design today

The design field is constantly evolving to keep pace with change: technological, social, cultural, and political. The past decade has seen the widespread adoption of design thinking, the popularity of design sprints, and the emergence of more accessible design tools. These shifts have had a democratizing effect, opening up the practice of design to an even more diverse array of individuals at all skill levels and becoming more inclusive and participatory.

Putting design tools in the hands of non-designers means the reach of the human-centered ethos has expansive potential to help us untangle some of our world’s most wicked problems. These tools and methods are purpose-built for helping us to navigate ambiguous situations and uncertain outcomes. They’re designed to ground our work in empathy, curiosity, and experimentation. Now, non-designers are empowered to be proactive and hands-on participants in the design process. Meanwhile, trained designers will be able to lean further into specializations and will also be called to step into influential roles as leaders, coaches, and change-makers.

In this article, we’ll sweep the landscape for compelling insights about how design is evolving, where it’s heading in the next few years, and what the emerging trends mean for you.

The future of emerging design frontiers

Since its inception in the 90s, human-centered design has grown to include a broad scope of problem-solving. Companies like IDEO — which is generally credited with formalizing this discipline — have long-applied design thinking in environments ranging from the C-Suite of Fortune 500 companies to NGO interventions in the developing world.

Design’s sphere of influence is only continuing to expand. Let’s look at a few interesting examples of how.

International Development

One standout example comes from the UK. Created in 2020, the Foreign Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) merged the government’s international development and diplomacy programs into a single department. For the past several years, the FCDO (formerly known as DFID) has partnered with the innovation agency Brink, to work at the intersection of emerging tech, innovation practices, and international development.

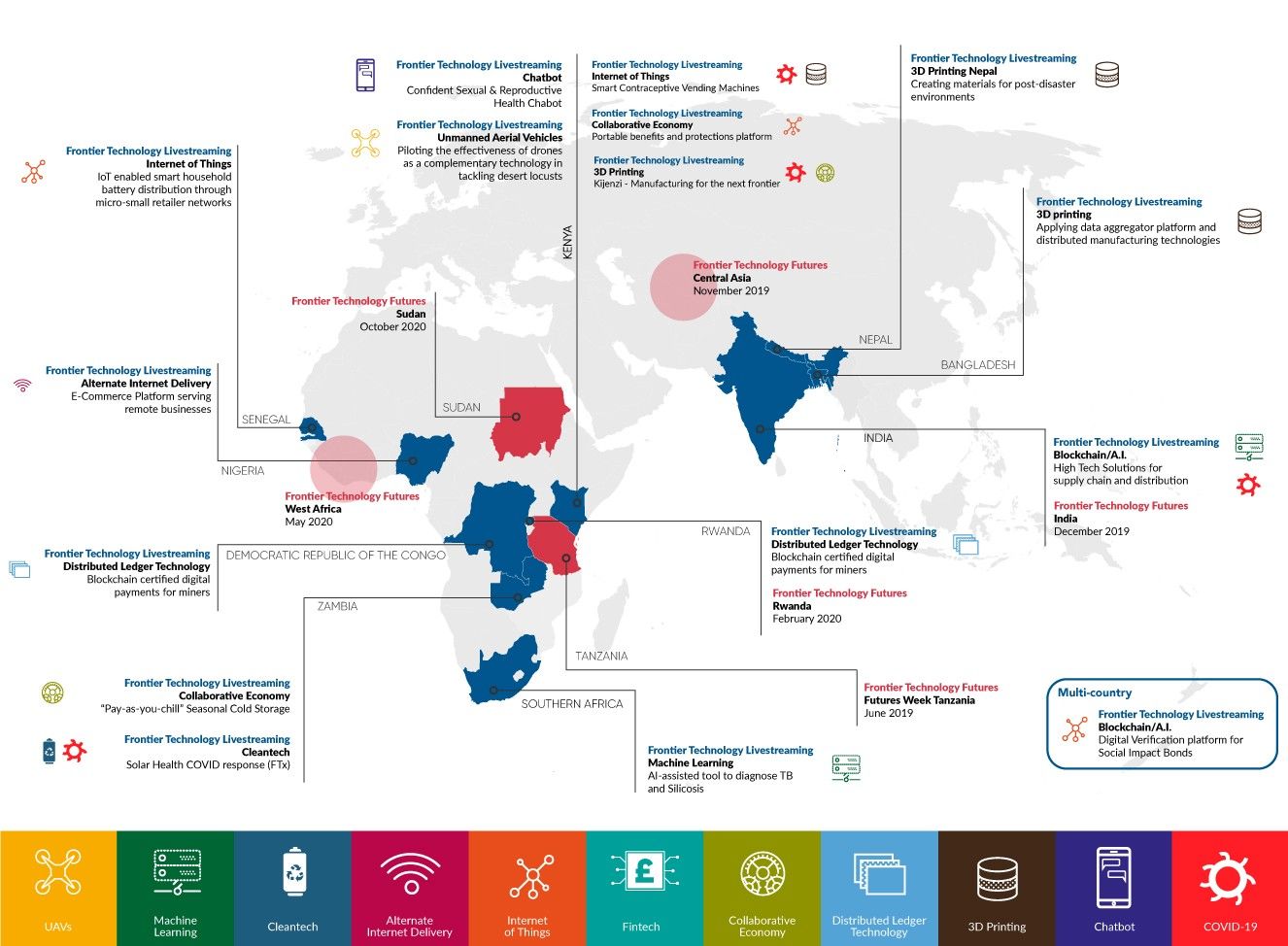

Brink’s Frontier Technologies Hub brings methods like Lean, Agile, and human-centered design, alongside governance and program management, to pilot and scale government-sponsored development initiatives all over the world. They do this in two main ways:

- The Livestreaming program is designed to field test “frontier tech,” e.g., blockchain, AI, and 3D printing, assessing its potential for positive social impact as well as the team’s ability to create scalable innovation.

- The Futures program is like a type of matchmaking, connecting tech pioneers with FCDO development experts to find a potential fit between technology and application and to enable experimentation in the field. This might be facilitated by embedding new technologies in existing programs or through running design sprints and smaller pilot programs for rapid testing and learning.

Overview of Frontier Tech Livestreaming’s operational pilots and Futures engagements as of January 2021. (Source)

Public Interest Technology

In December 2021, President Biden signed an Executive Order addressing the critical need to dramatically improve the quality and accessibility of government services online. According to a recent Fast Company article, “The EO takes the extraordinary step of prioritizing the needs of the people over the needs of federal agencies’ stated purposes...It also smartly focuses on customer service rather than digitization. Sometimes an answered phone call might be just what someone needs, rather than a spiffy website or app.”

This order demonstrates service design thinking at work, where looking at every user touchpoint — whether digital or physical — reveals opportunities for improvement that meaningfully prioritize customer needs.

The Future of Work

COVID may have triggered some dramatic shifts to our working lives, but we’re continuing to negotiate new norms and reset expectations for our relationship to the workplace. A Gartner trend report notes that to keep pace with continuing change, companies will need to focus on designing their organizations for resilience and adaptability over the traditional focus on efficiency.

Organization design is following service design as the discipline’s next paradigm shift. Borrowing from the design thinking toolkit, org designers “work with teams, in their native environment, to identify opportunities for improvement and test the fit of potential new ways of working.”

McKinsey describes three “symbiotic elements” involved in envisioning the future of work, setting up org designers’ core challenges:

- The value proposition of the workplace: How do we make money?

- Balancing human resources for existing and future needs: Who do we have, and who do we need?

- Reimagining workspaces, not just physical, but also ways of working, norms, and values: How and why do we work?

As this discipline grows, organizational designers will apply their skills to reimagining structures, processes, spaces, how we source and cultivate talent, and, of course, the tools we use to collaborate and communicate.

Core Curriculum

Stanford’s d.School, official home of design thinking and methodology, has always had an open-source approach to sharing its rich educational resources. Indeed, their vision statement declares: “We believe everyone has the capacity to be creative.” Through continuing education programs and the prolific publishing of tons of toolkits and resources, they’ve done much to democratize access to valuable design thinking learning materials.

As a result, design thinking has extended to reach students in classrooms from kindergarten through med school. Design thinking as a pedagogy is being adopted into core curricula around the world. At California’s Nueva School, students begin learning design thinking methods in primary school, beginning with a “16-week design thinking challenge to build an LED lamp for someone in their lives who needs light.” In middle and high schools, students tackle open-ended explorations of timely issues, like “How might the world sustainably feed itself by 2050?”

In 2017, the University of Texas at Austin launched “Radical Collaboration,” a three-hour design thinking seminar available to undergrads from colleges across campus. The program is part of the school’s mandate to transform creative education for 21st-century careers. Taught by IBM designers, students participate in a semester-long training program onsite at the IBM Design Studios in North Austin. The program has already spun off a focused Design Institute for Health in partnership with the UT: Austin’s Dell Medical School and the College of Fine Arts.

The future of designing with AI

Machine learning is radically reshaping product and service development. The design opportunities available through the different fields of artificial intelligence (AI) are essentially limitless. But before we dig in to where all of this is headed, it’ll be helpful to briefly cover the key concepts of AI in design.

The terms machine learning and deep learning are often used interchangeably. The main difference is, well, depth. Overall, machine learning is an “attempt to simulate the behavior of the human brain by allowing it to ‘learn’ from large amounts of data.” Everyday life is increasingly inclusive of products and services shaped by deep learning technology; think digital assistants like Alexa, facial recognition software, or your Spotify “Discover Weekly” playlist.

Computer vision processes visual inputs — including digital images, videos, and websites — recognizing patterns and deriving meaningful information from which it can take action or make recommendations. Uizard uses computer vision to power our design assistant, which allows us to translate hand-drawn sketches into digital files with editable components or scan visual inputs and extract styles to create custom themes.

If you’ve had a conversation with a customer service chatbot or asked Siri to tell you a joke, you’re experiencing the result of Natural Language Processing (NLP). The main challenge of NLP is the nuances of understanding the meaning, intent, and sentiment layered in human language and exchanges. In other words, how can one convey “personality” without a person? The design team of CapitalOne’s award-winning bot, Eno approached it this way: “They also decided to make sure that Eno had human-like characteristics, but was completely transparent about being a bot..if Eno had a bumper sticker it would read, ‘Bot and Proud,’ because that’s part of Eno’s character.”

However, with great power comes great responsibility. The growing presence of AI in our lives requires an ethical grounding. What are our human rights when our faces, bodies, and voices become data? Where do we draw the line between privacy and freedom? For example, in the States, the IRS is backing away from asking users to upload selfies to access information on the government platform. Though it wasn’t an explicit requirement, it still drew questions and concerns around how the data would be used, stored, and protected.

Distinguished professor Genevieve Bell, who started Intel’s User Experience Group in 2005, and now runs the Center for Humane Technology, poses six ethical questions about the future of AI. The last and most critical question she asks is: “What's its intent? What's the system designed to do and who said that was a good idea? Or put another way, what is the world that this system is building, how is that world imagined, and what is its relationship to the world we live in today? Who gets to be part of that conversation? Who gets to articulate it? How does it get framed and imagined?”

In many ways, the buck stops with the designers who are responsible for shaping the interface layer (tangible or otherwise) of our interactions with intelligent systems. We are starting to see the emergence of organizations and dedicated practices focused on establishing the principles of an ethical AI, such as IBM’s Design for AI group, or the UK-based company Humanising Autonomy, which “envisions an ethical society in which the value of automated systems is measured by how well they promote the safety and well-being of people.”

The future of design in the Metaverse

We know. Everyone is talking about the Metaverse and how it’s poised to transform life as we know it. But...what is the Metaverse exactly? The satisfyingly simple answer is that it’s a “virtual reality version of the internet, a hypothesized version in which users can engage with one another as well as the computer-generated environment that surrounds them.” So, basically a game, like the Sims or Fortnite? Yes, and...

Indeed the Metaverse draws on the world-building and spatial computing of game engines. But as a kind of parallel society (or an Extended Reality, aka XR), it’s also applying principles of decentralized governance and creating a wholly digital economy with cryptocurrencies, blockchain contracts, and digital assets like NFTs (non-fungible tokens).

Given this opportunity to effectively create a whole new world (or worlds), the Metaverse is ripe with design potential. The past year has already seen explosive growth in the digital art market with NFTs. In March 2021, a JPG collage by the artist known as Beeple sold at a Christie’s auction for $69 million USD. In November, Amsterdam-based “digital fashion house” The Fabricant debuted its first collection. Artist Krista Kim sold the first NFT-backed digital home Mars House, and digital artist Andrés Reisinger and architect Alba de la Fuente partnered to create Winter House, a virtual Metaverse residency.

Winter House [Source] © Andrés Reisinger

Say design duo Tin&Ed, “We hope that the metaverse is a place where we can co-create a more equitable reality, not one where we escape our existing reality.” Co-creation is integral to the concept. In an interview, Tim Sweeney, CEO of Epic Games, emphasizes that “the meta universe ... does not come from any industry giant, but the crystallization of the co-creation of millions of people.” In fact, we should be wary of companies and brands seeking to dominate the metaverse and the prospect of transferring the same problematic models of interaction and sociality to a new platform.

The future of responsible design

“The ultimate hidden truth of the world is that it is something we make. And could just as easily make differently.” These are the words of David Graeber, the late American anthropologist and activist known for his instrumental leadership in the Occupy movement. This quote was notably used in the opening of filmmaker Adam Curtis’ documentary, “Can’t Get You Out of My Head,” and it seems like it’s speaking directly to designers, or any one of us, really. As we’ve been discussing, human-centered design has reframed our understanding of the nature of design as a way of looking at the world and given us a set of tools to help us try and change it.

But we are still prone to blind spots. The practices of service design and organizational design have been helping us to zoom out from a micro-focus on individuals to a macro view of complex systems and dynamics. Being able to take this broad view enables us to consider a more inclusive scope of all the stakeholders involved and, thus, the rippling effect of our decisions. Now, we must go even further, thinking not only about our present stakeholders and ecosystem but also our future ones.

Responsible design asks us to think about the long-term real and hypothetical impacts of design decisions we make today. We must operate from a position of strategic foresight. As Albert Shum, CVP of Design at Microsoft’s Experiences & Devices Group, suggests, “Asking ‘what could go wrong?’ should never be a hypothetical question, but a design requirement to answer.” Today, we kickstart our design process by asking, ‘how might we,’ but now, principles of Responsible Design nudge us to also ask, ‘at what cost?’